Only 7,100 cheetahs remain in the wild, and the population is declining.

Cheetahs have almost been wiped out across Asia, with fewer than 50 animals living in three small pockets, all in Iran. Now, the African population is also moving perilously close to extinction.

Cheetahs need large ranges of hundreds or even thousands of square miles – protected reserves across Africa alone don’t offer enough land to keep the animals alive in significant numbers. Today, three-quarters of cheetahs’ ranges are found outside protected areas, supporting two-thirds of the global population.

That makes them especially vulnerable to human-wildlife conflict, to overhunting of their prey, and to the loss of wilderness areas to farmlands, settlements and roads. Farmers often kill cheetahs, especially if the growing scarcity of their prey forces the cats to attack livestock. They are also often mistakenly blamed and killed by farmers, when larger carnivores like lions and hyenas have killed livestock.With climate change and population growth putting increasing pressure on the environment, cheetahs face unprecedented threats to their survival.

But cheetahs also face significant threats from the illegal wildlife trade. They are poached for their skin and increasingly to be kept as pets, especially in the Middle East.

Cheetahs: disappearing fast

Down 50 percent

There are only around 7,100 cheetahs alive in the wild, down from around 14,000 in 1975 and about 100,000 a century ago.

77%

of current cheetah ranges are situated outside protected areas, making the animals especially vulnerable to human-wildlife conflict, overhunting of their prey, habitat loss and the illegal wildlife trade.

9%

of cheetahs have been driven out of 91 percent of their historic range, with only 9 percent left.

Cheetah facts

- Cheetahs are the fastest land mammals. They can run more than 100 km an hour, but only in short sprints.

- They try to creep up to within 50 metres of their prey before the final sprint, with hunts often lasting only 20 seconds. They usually hunt gazelles, impalas and baby wildebeest, as well as small mammals and birds.

- Their running style is similar to a greyhound, arching their backs and pulling in their feet before uncurling their bodies like springs. They use their long tail as a rudder to help then change direction, with all four feet completely off the ground half the time.

- Unlike other big cats, they never roar and can’t fully retract their claws – along with special pads on their feet, their claws give them traction to change direction at high speed. They also have an enlarged dew claw which they use to trip their prey in a chase.

- Females are solitary, looking after litters of three to five cubs for up to two years. Mum will sometimes bring her cubs a live baby antelope for hunting practice.

- Brothers sometimes stay together for life. Most males are solitary but some form small cooperative groups. The most famous group is the Fast Five, or Tano Bora, who live in Kenya’s Masai Mara and work together to take down large prey like adult wildebeest.

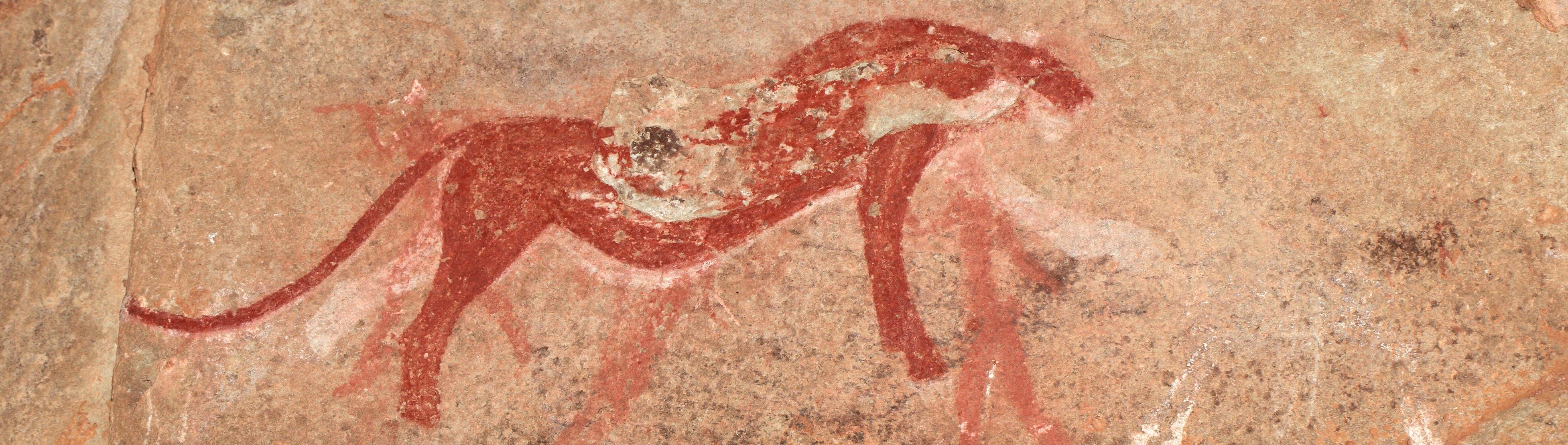

Cheetahs in African culture

A Zulu folk tale suggests a reason for the dark marks beneath cheetahs’ eyes. They are, the story goes, the track of a female cheetah’s tears, after a wicked and lazy hunter stole her three cubs. Fortunately, the story has a happy ending, with an old villager exposing the wicked hunter and turning the villagers against him. The lazy hunter had broken the traditions of the tribe by stealing the defenseless cubs: he was driven out of the village and the cubs returned to their mother.